It was the Walnut finish of this simple mantel clock that caught my attention. Finished with fine brass inlay, the clock I feel has a Georgian appeal. Clearly its patina, and evidence of having spent some time without attention, had a great deal of appeal.

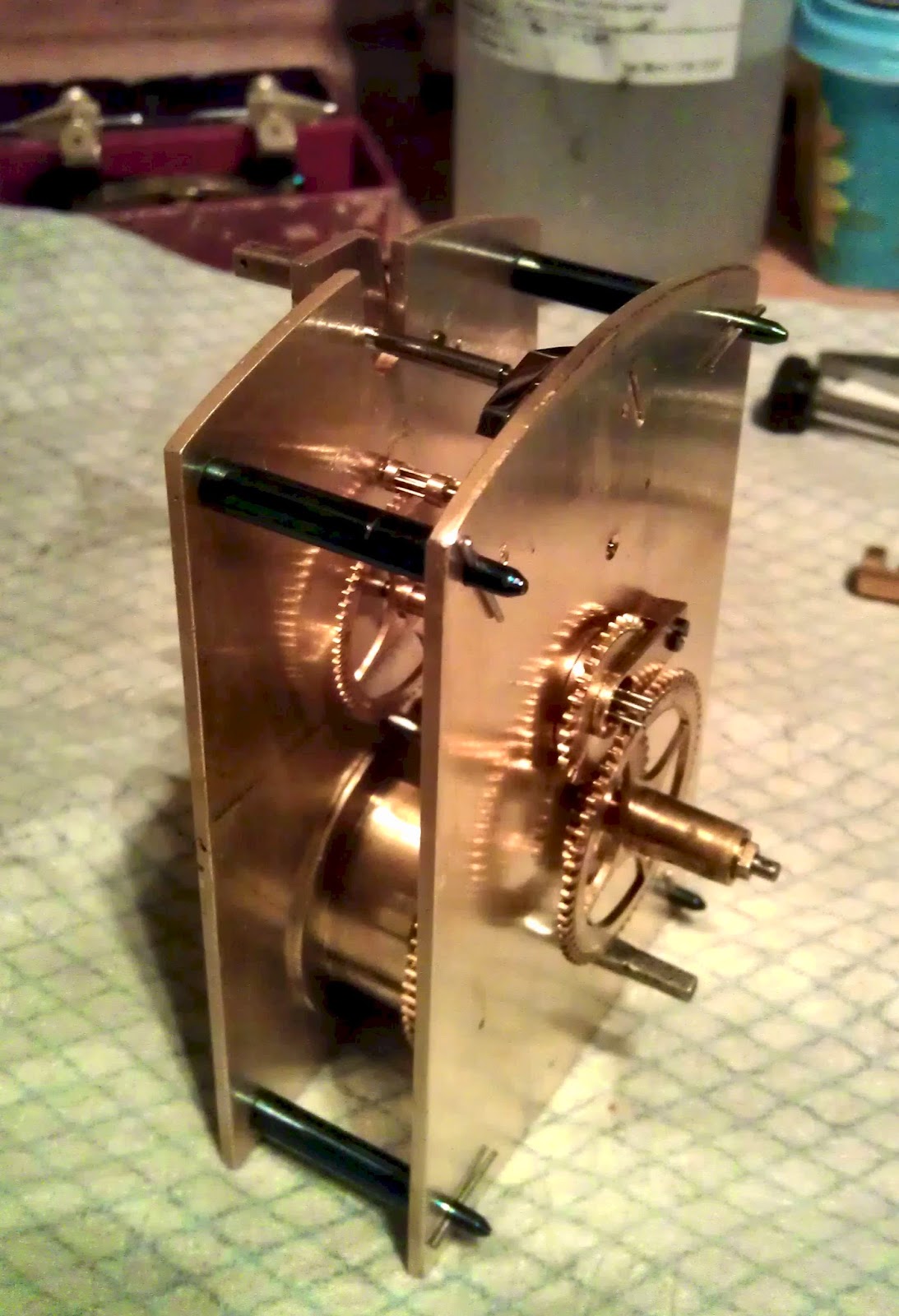

Examination of the movement has led me, and other friends from the horological world, to question if this movement is an early Winterhalder and Hofmeier, or if it is an English movement. Winterhalder and Hofmeier are known to have copied some English movements in their production. So the jury is out, if anyone has any comments regarding this please do email me.

The case would receive limited attention in order to retain its original appeal, pic 2 below shows brass inlay missing. The glass was missing, and there is evidence on a previous attempt to clean the dial. Smudging of the paint can be at numbers 4,5 and 6.

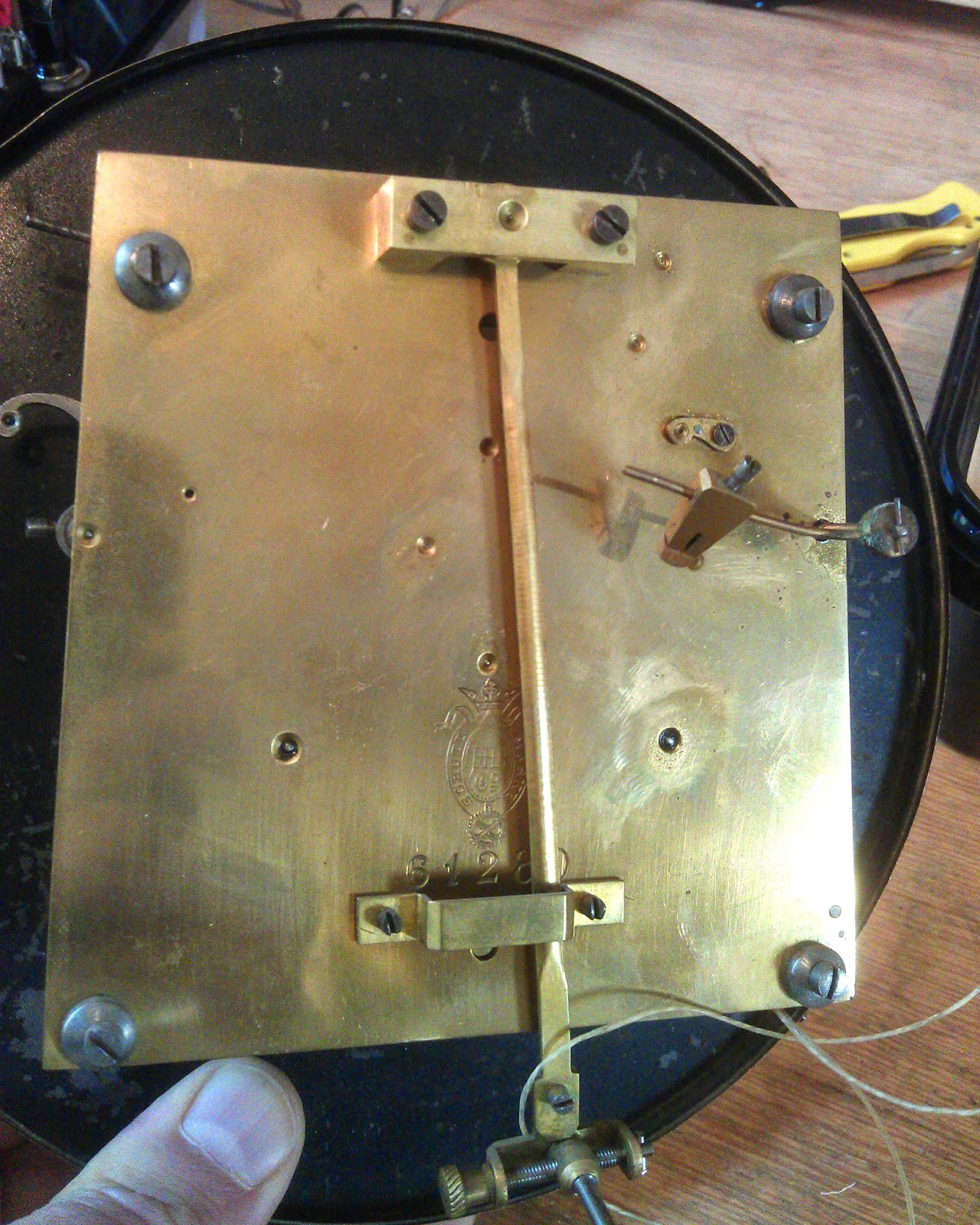

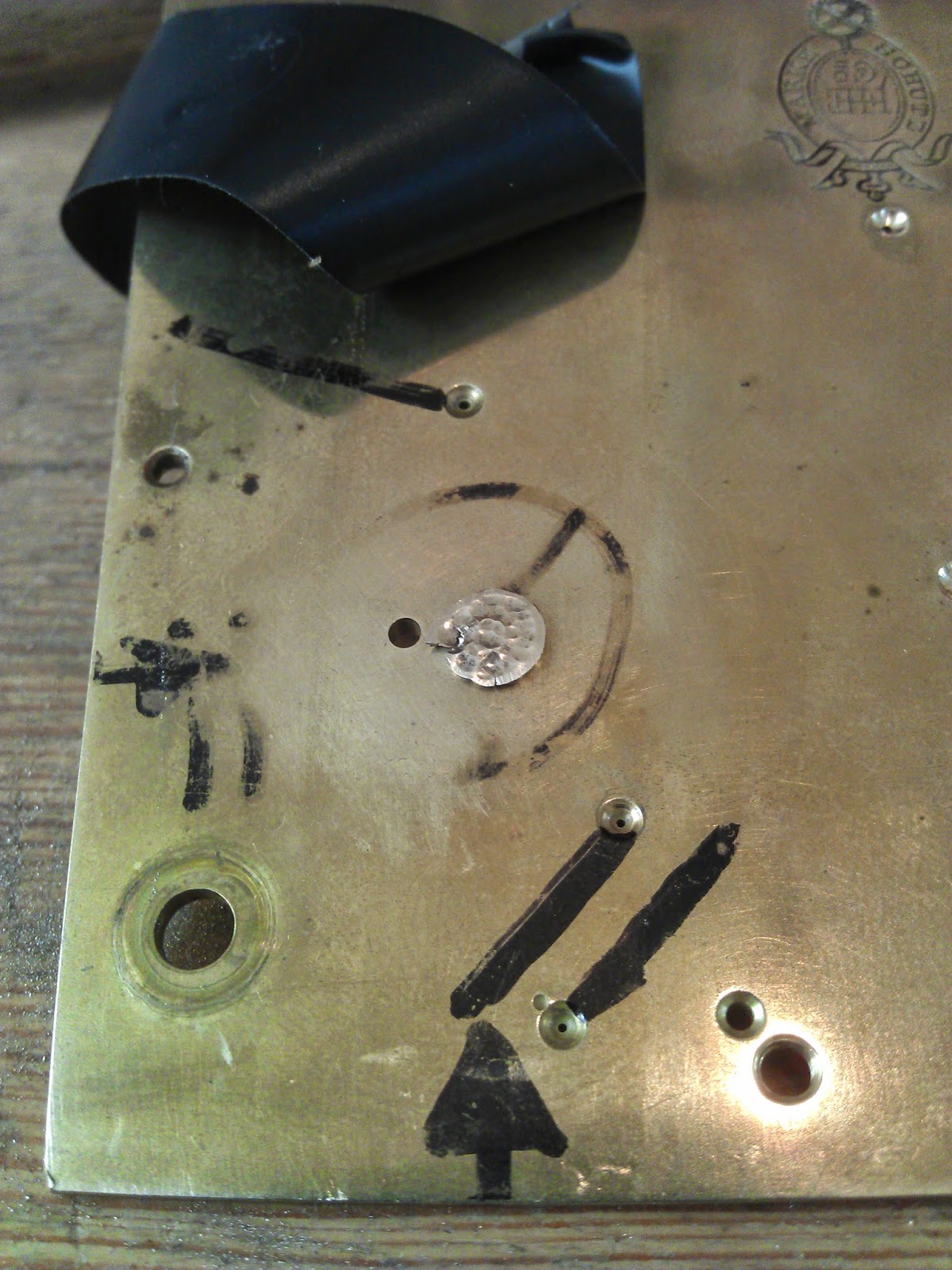

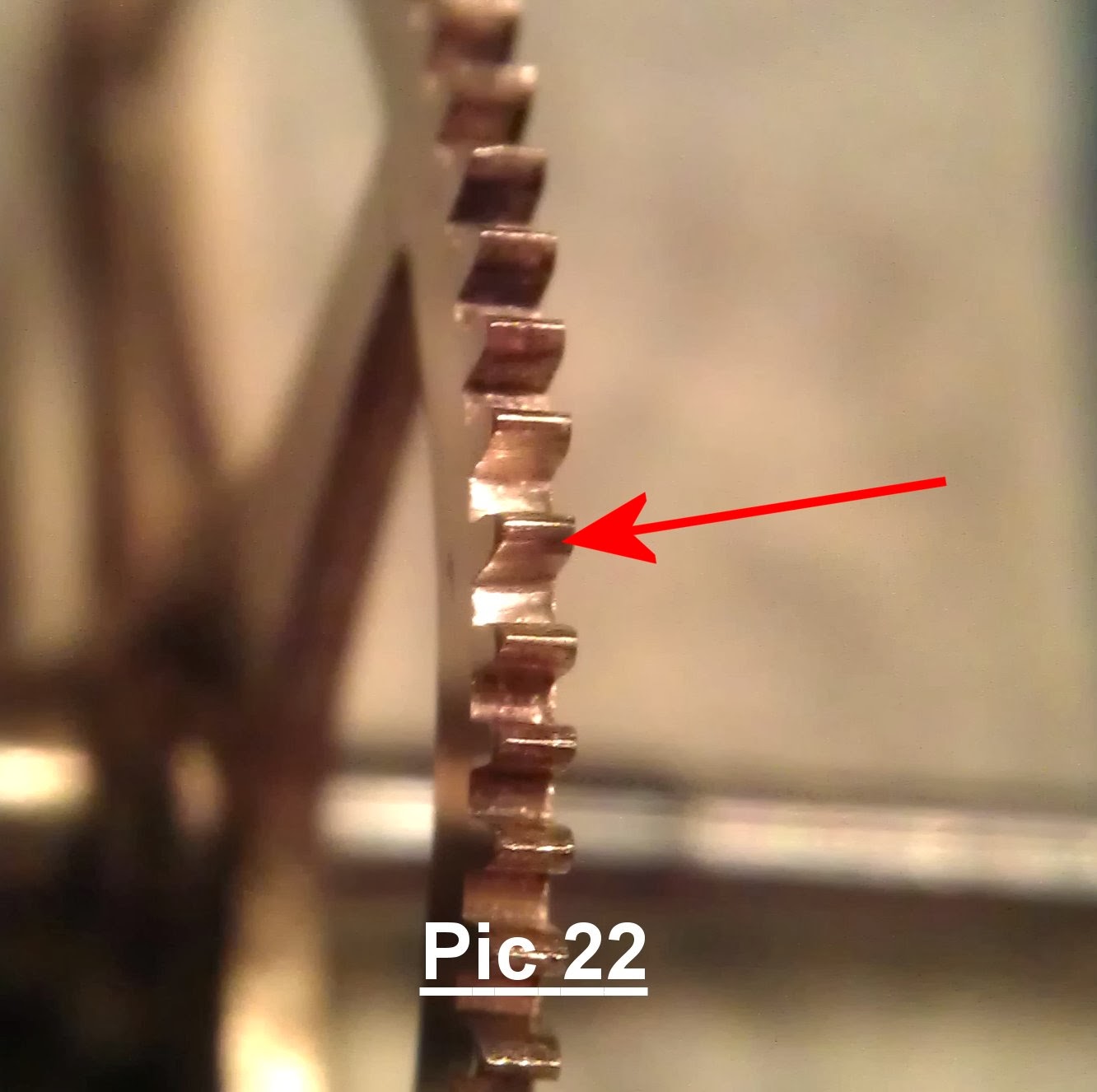

I noted that the stops works on the back plate of the movement, was damaged. The pictures below show that the pinion leafs have been filed off at some point. I would imagine that this was done to lengthen the running time of the clock. With the stop works complete it would run for approx 30hrs.

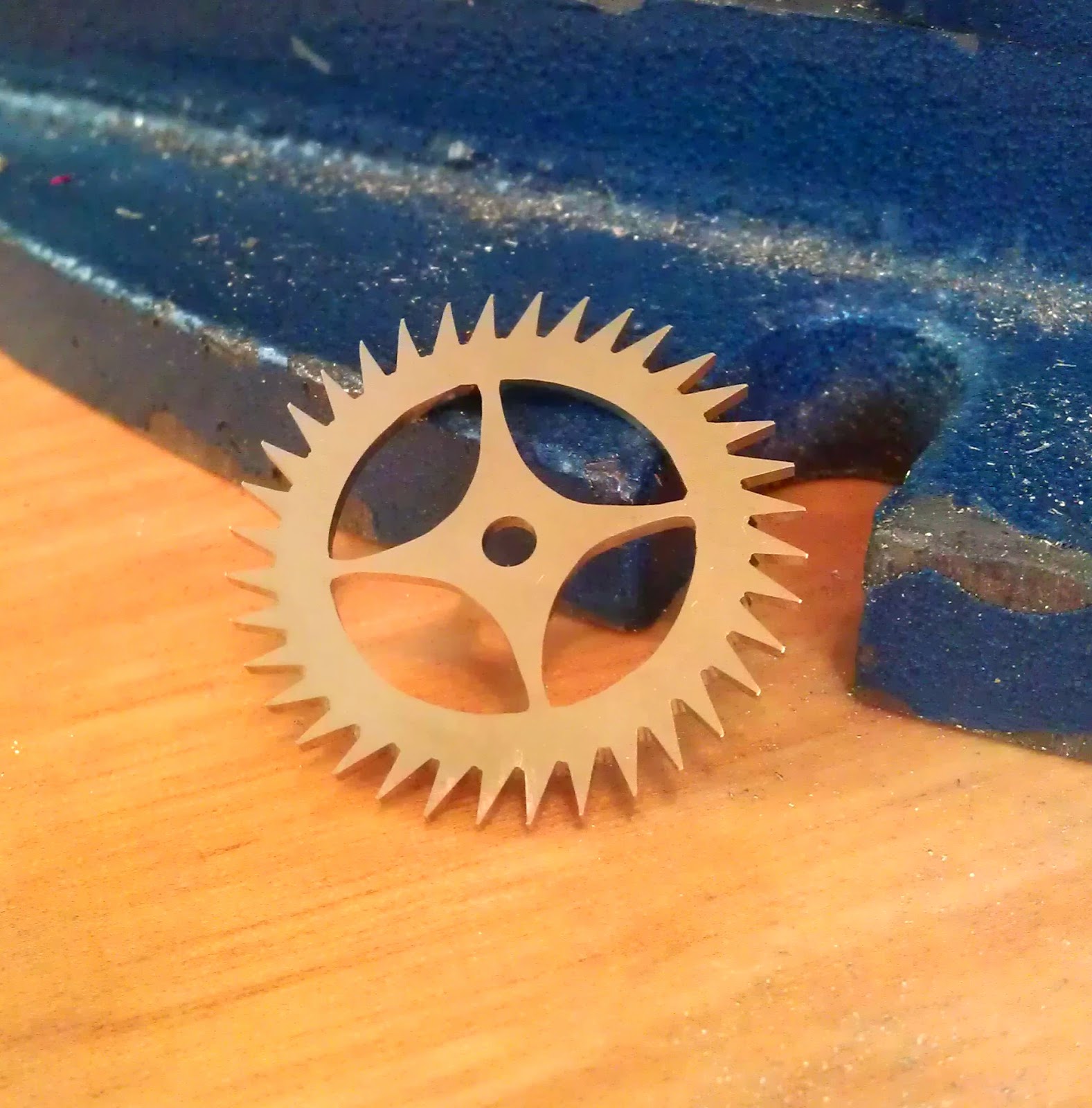

Whilst I appreciate the benefit of a longer running clock, sympathetically restoring to original where appropriate is preferred. To this end I handmade a replacement pinion for the stop works. The stops works would enable the movement to use a more consistent section of the springs power curve, by avoiding the use of the first two winds and the last few winds. So, in theory, be a better time keeper. Completed pinion below, with a hole for fitting to its post with a pin.

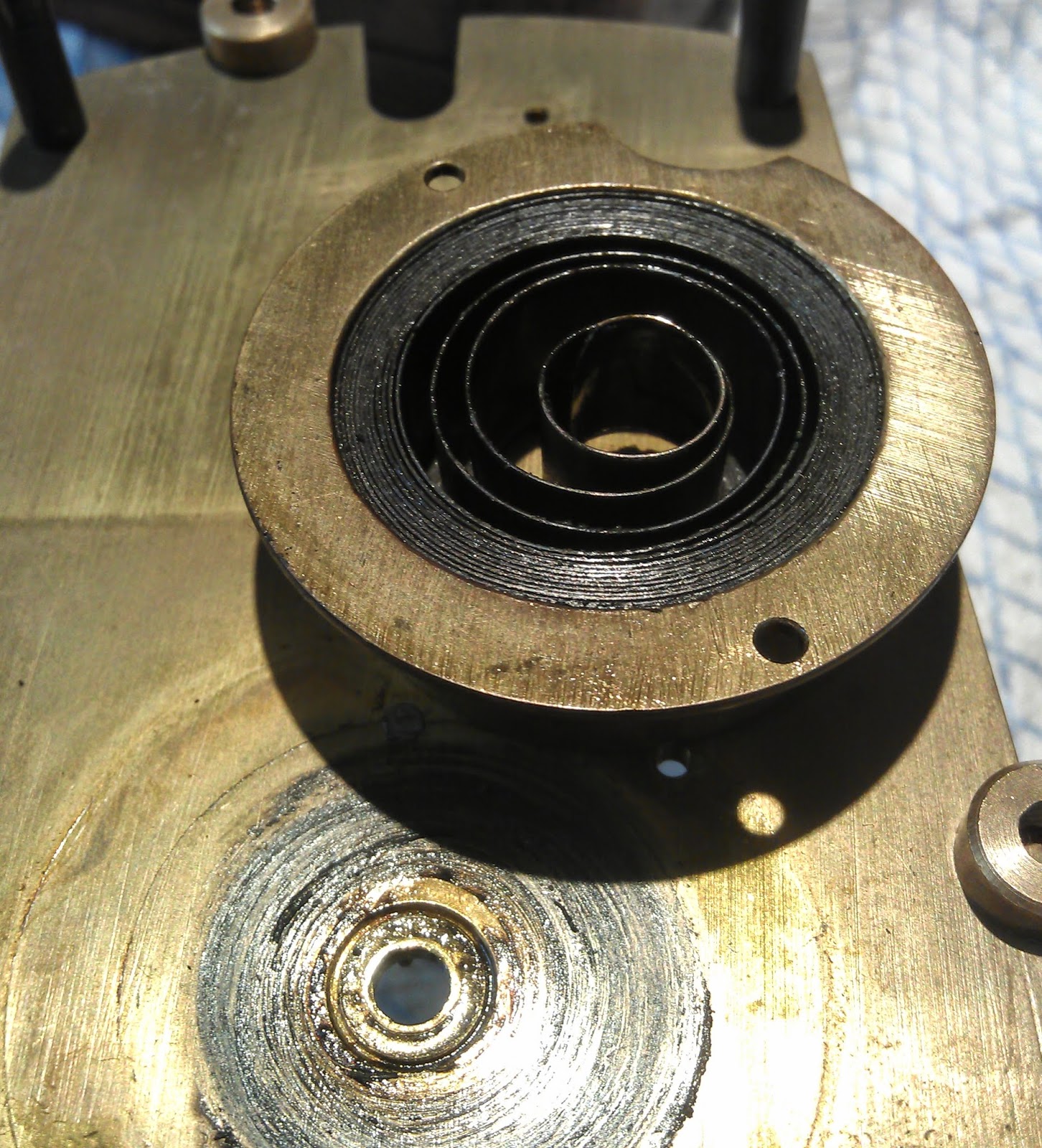

I heard some 'rattles' coming from the bottom of the case, and on closer inspection, I found a number of small brass teeth. This would explain why the winding arbour turned without resistance. They would be the teeth from the ratchet wheel, having suffered a spring incident. The pictures below show the state of the internal ratchet wheel, with missing teeth, and the 'hung' spring barrel. The 'hung barrel' is fixed to the clock plate.

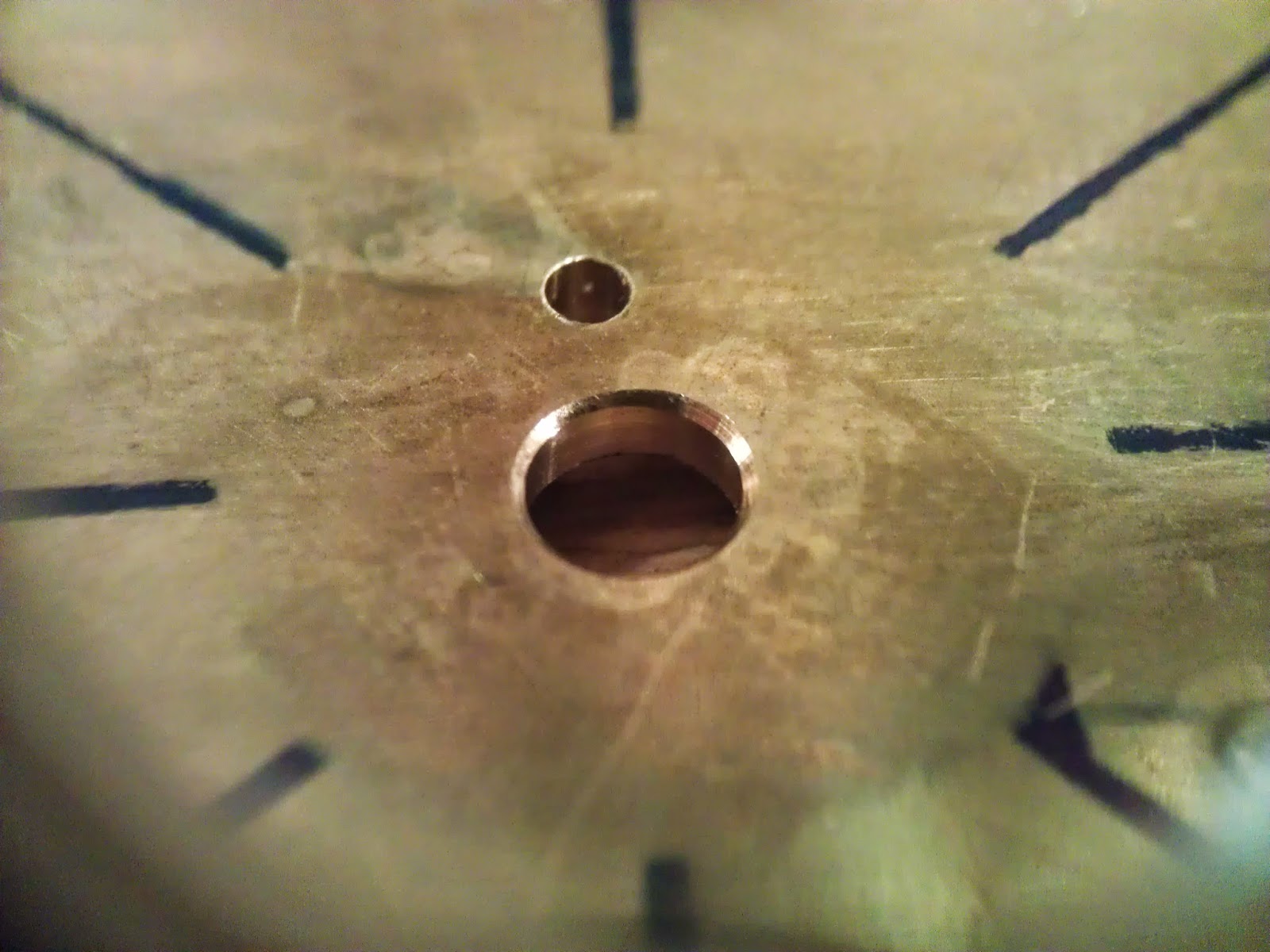

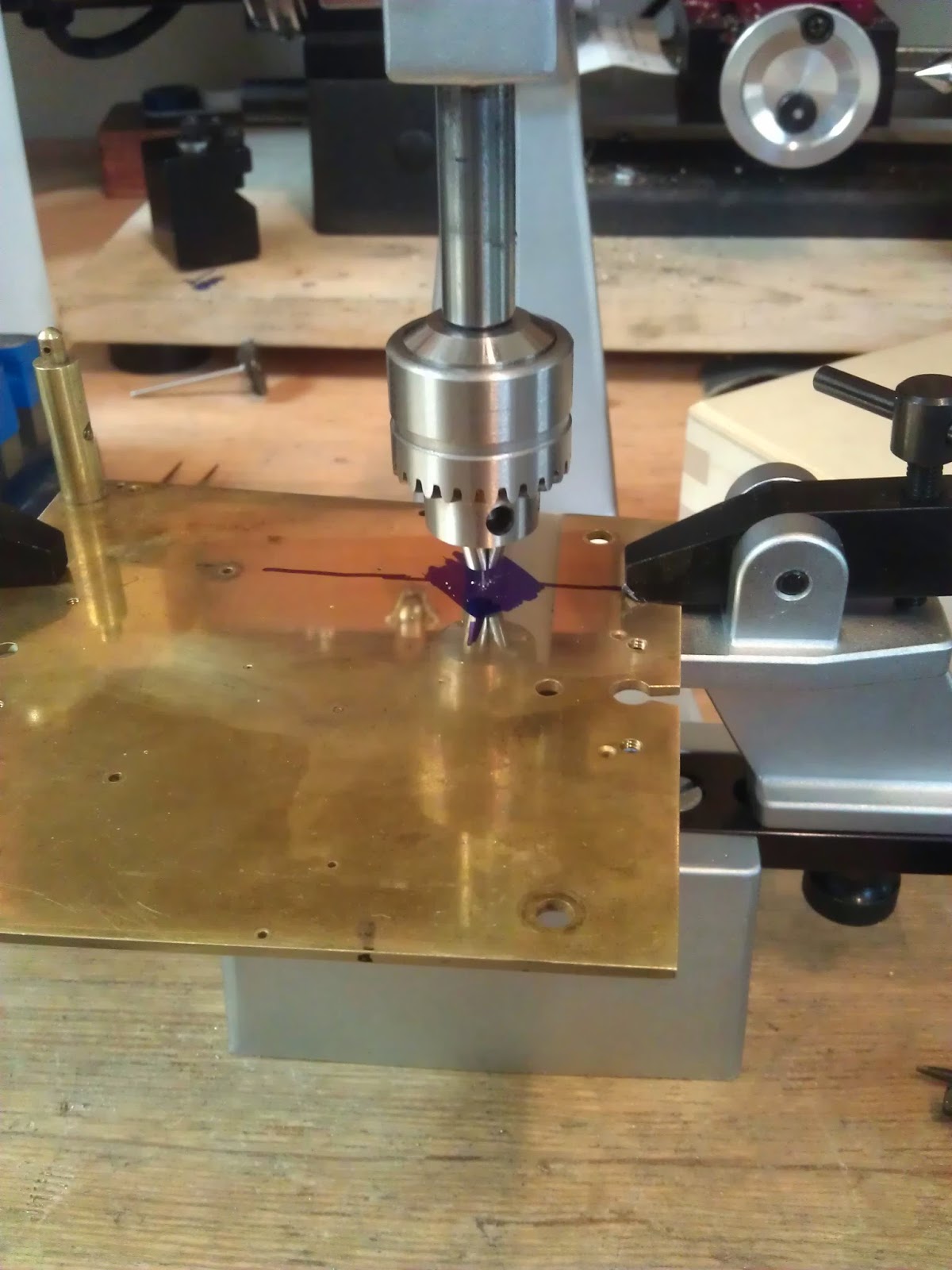

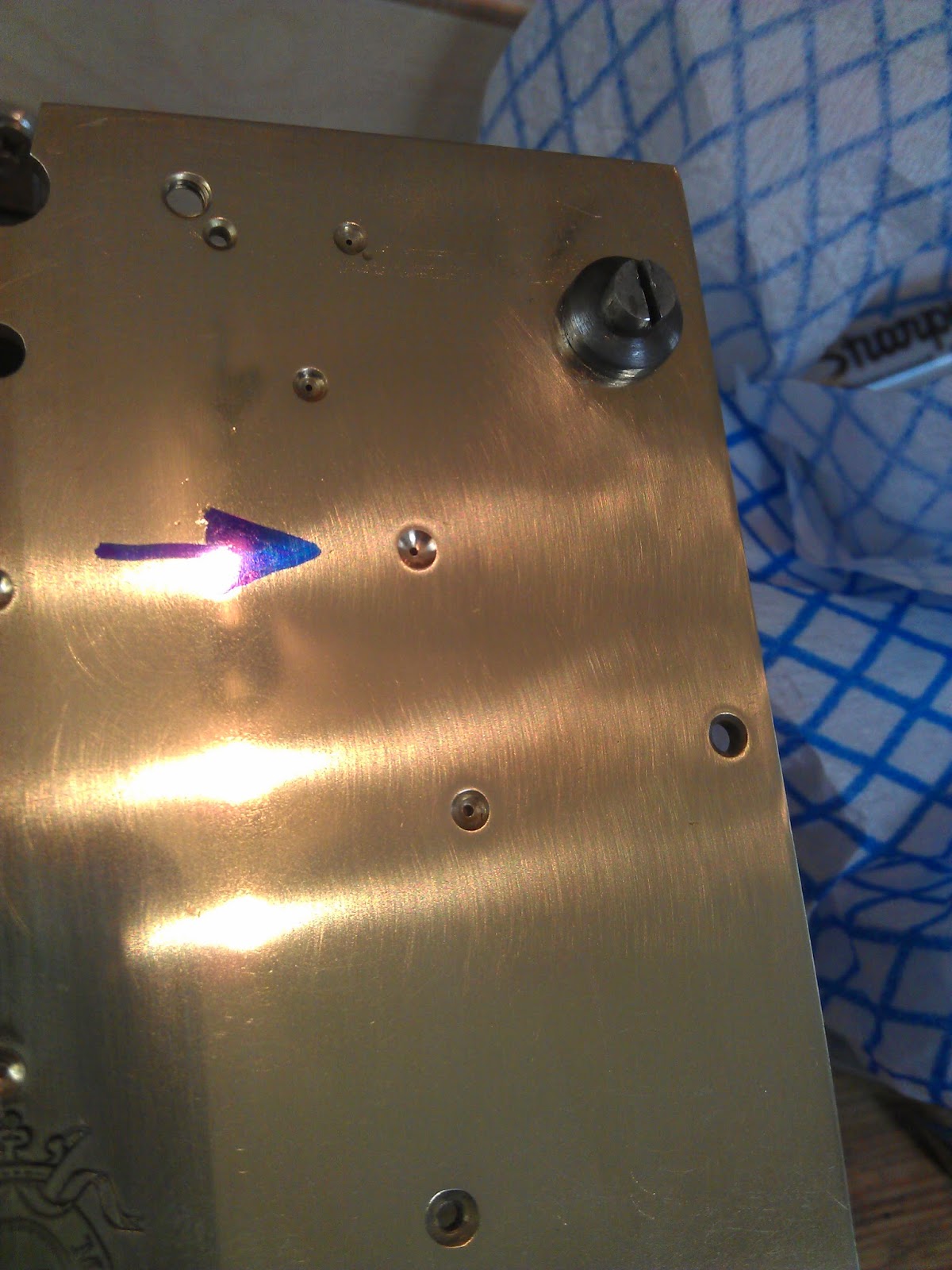

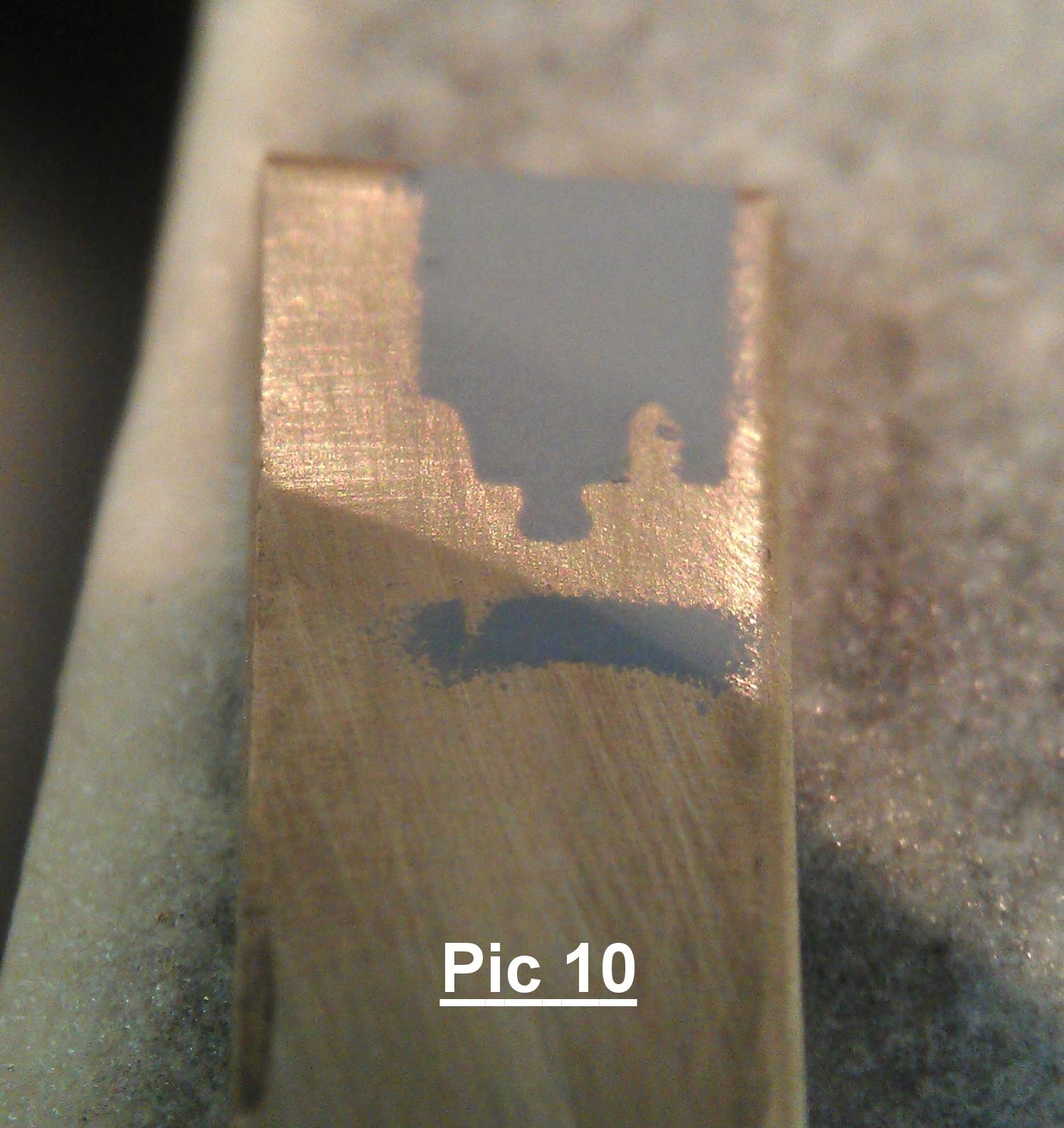

I had a choice, whether to make a complete new unit of ratchet wheel and pipe, or use a new ratchet wheel and keep the original pipe. I chose the latter, though making a completely new unit would be quicker, keeping as many parts original is always the way forward where able. The pipe was mounted in a lathe, and the ratchet was cut off, up to the diameter of the pipe, in order to leave material to produce teeth to fit (rather like castle ramparts) into a new ratchet wheel. See pics below. Receiving slots were cut into the wheel to form a tight friction fit, which was strengthened by riveting and silver solder.

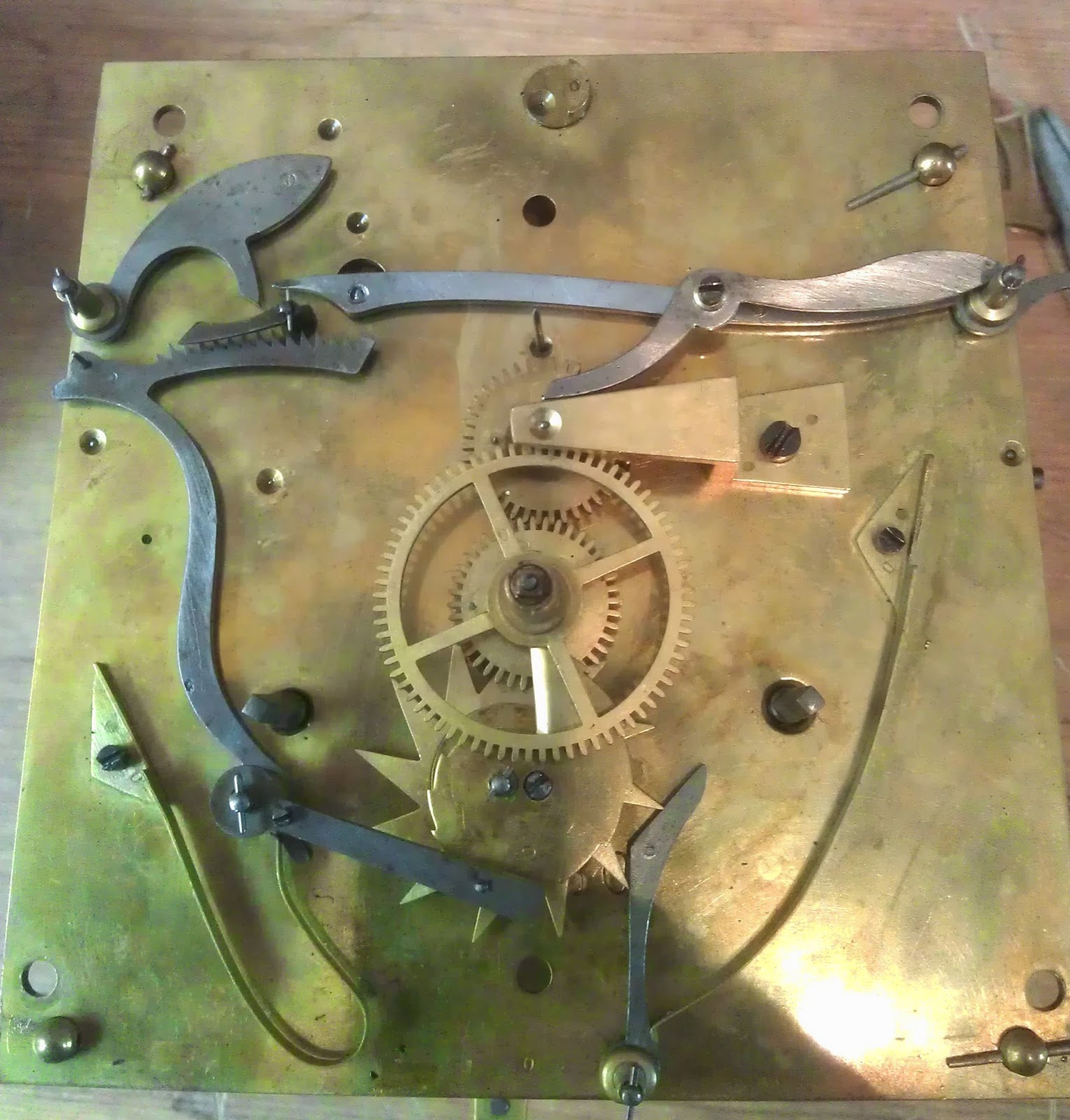

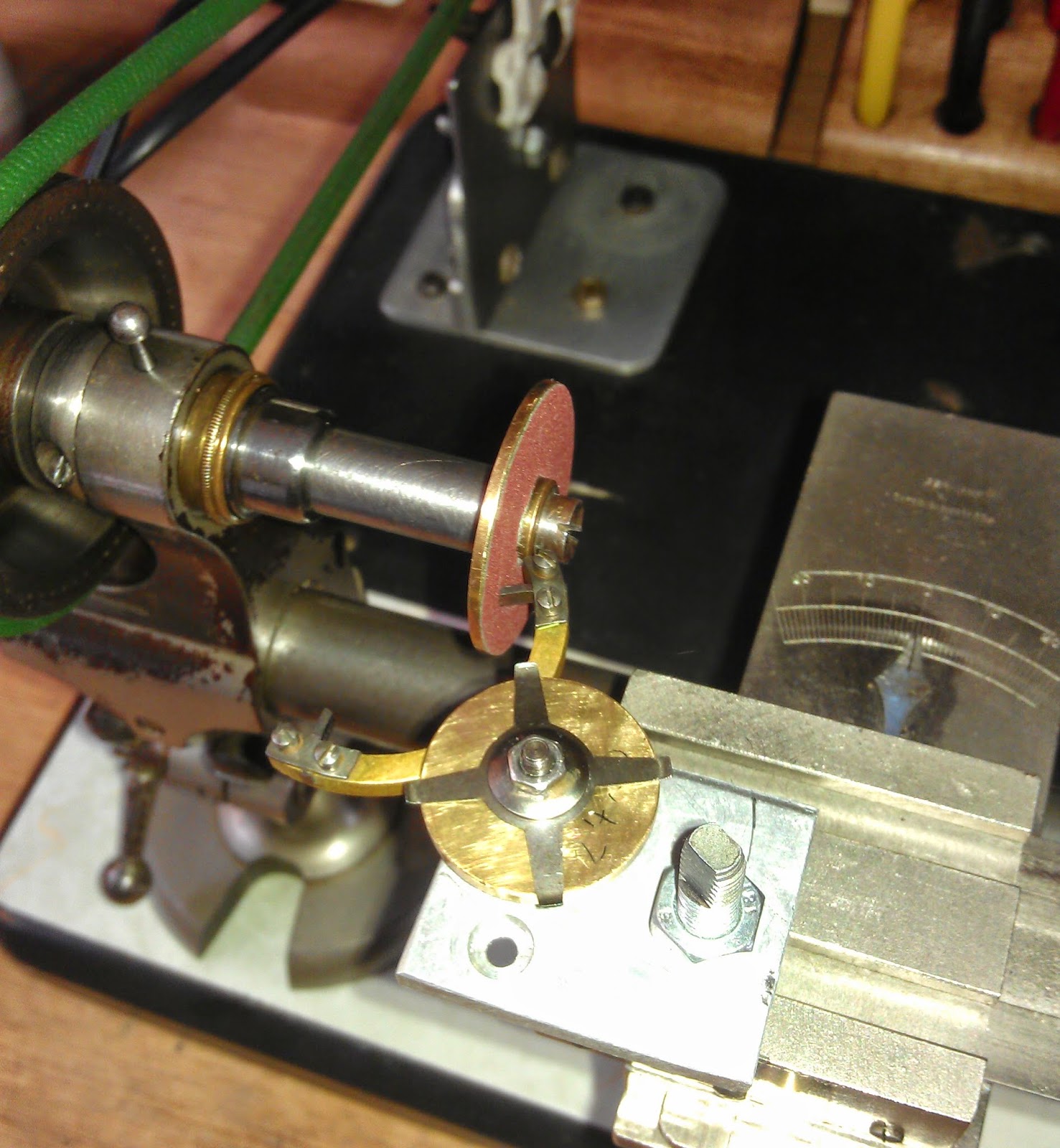

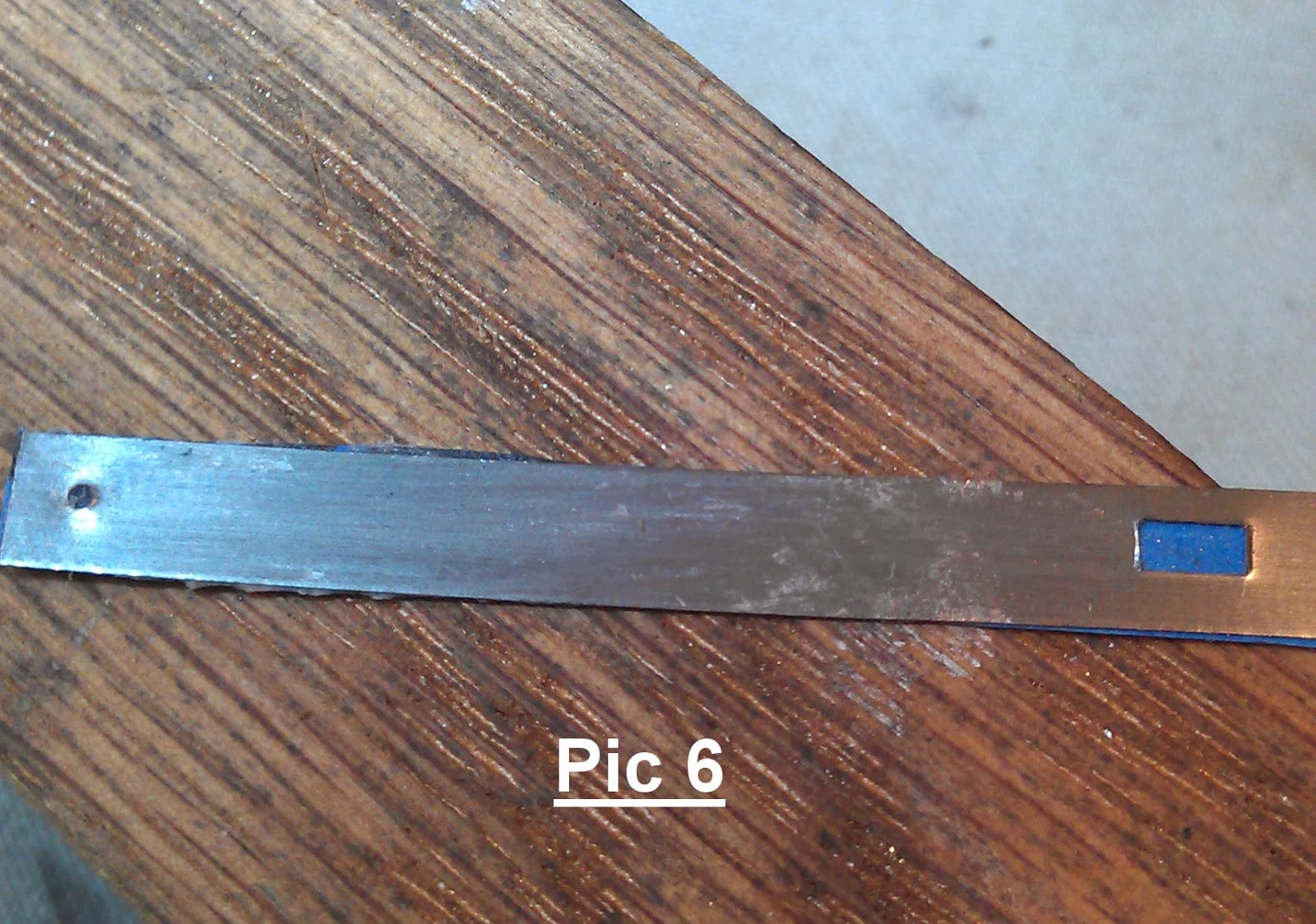

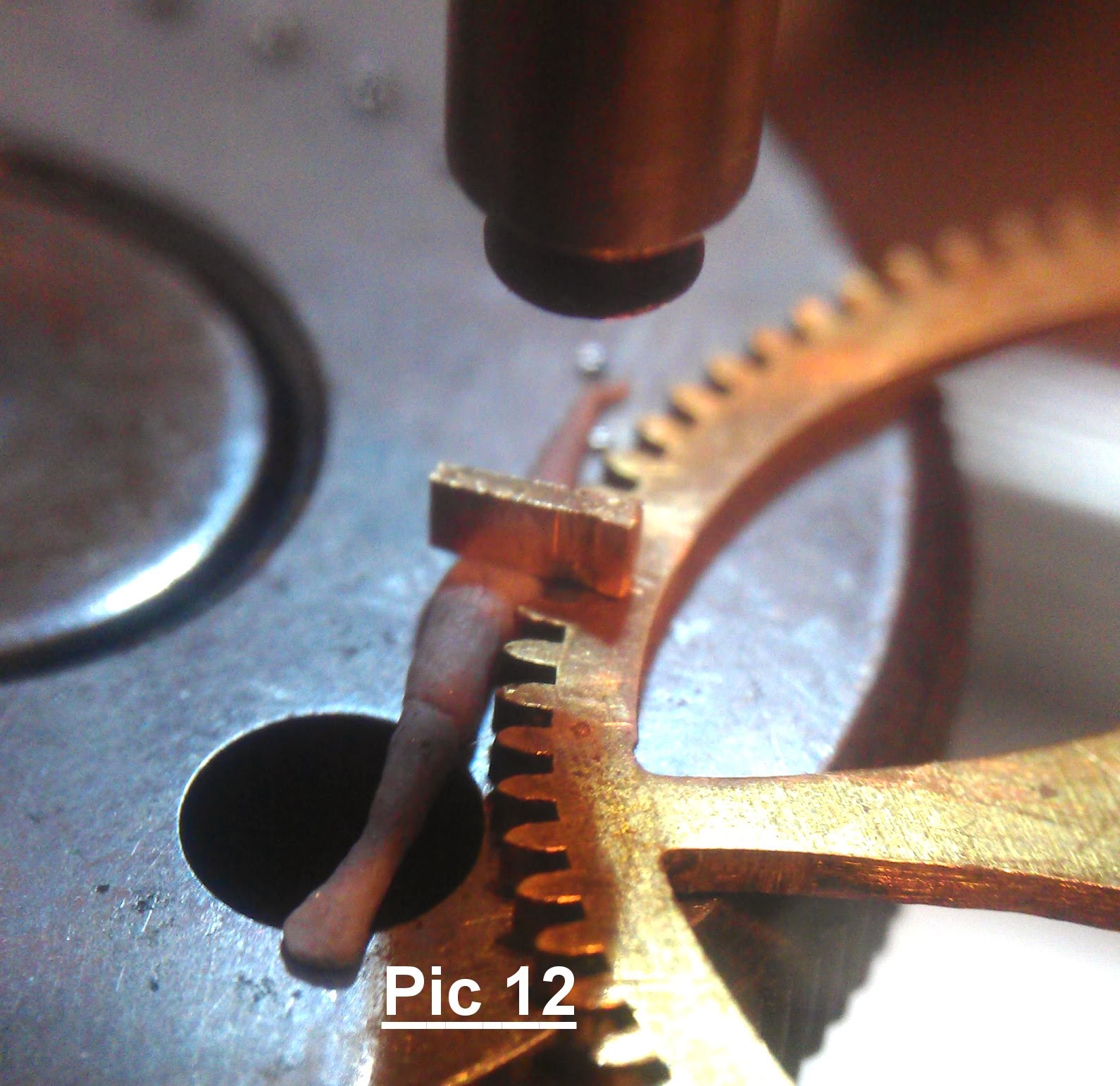

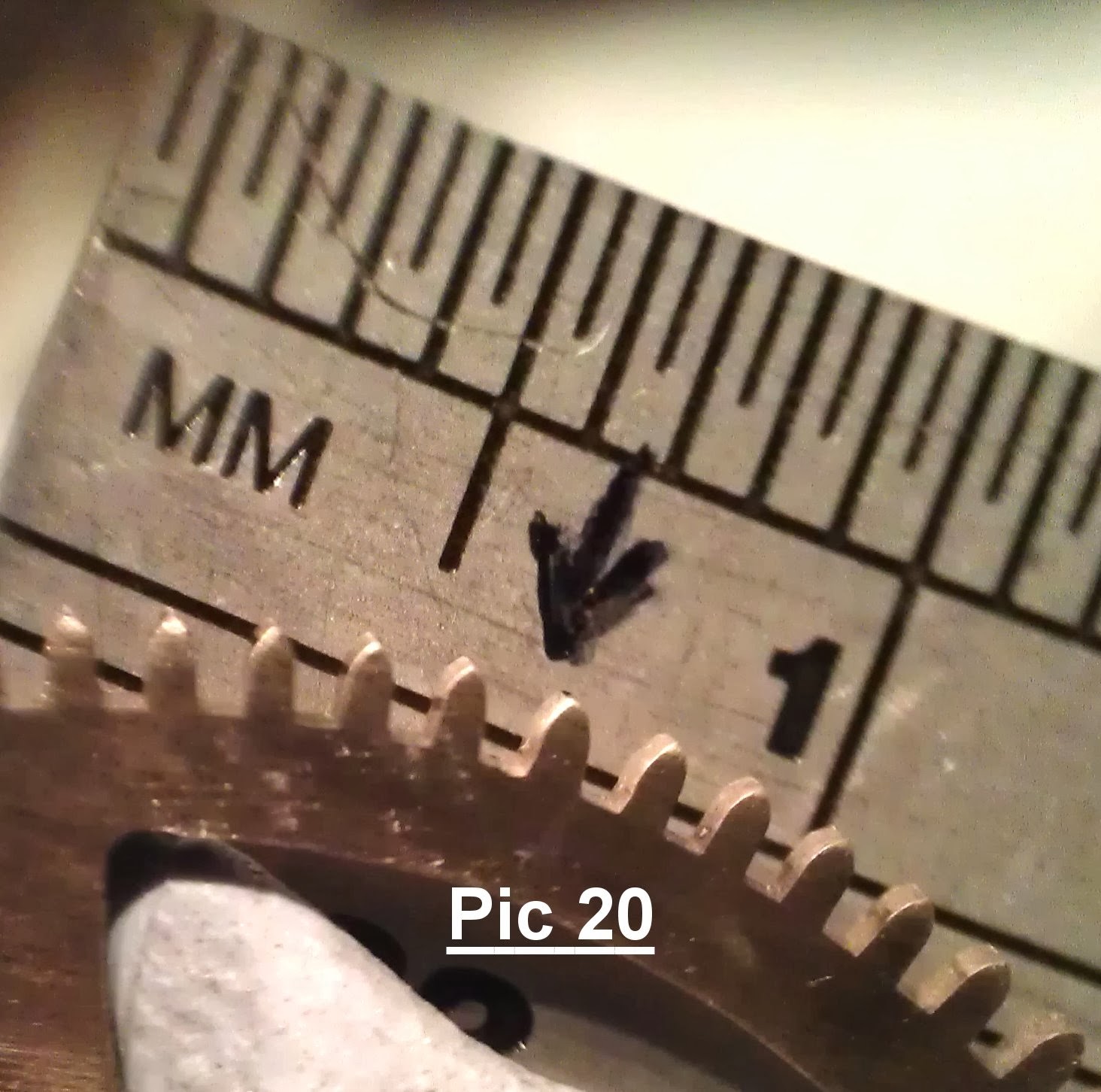

I wasn't expecting to find quite so much work needed on this time only piece. The escapement wheel had irreparable damage to it, with a few tooth tips broken. I also think that the teeth had been shortened at some point and an attempt made with the anchor to match for geometry. These led to me making a new escapement wheel by hand. It can seen in the pic below that the wheels inner cut outs maintain a hand made sense. Following this I made a new anchor from flat tool steel stock. Following being satisfied the geometry was correct, the new anchor was hardened, polished and tempered.

The lantern pinions required re-trundling given there was wear on them. I will let some wear go with these, however as soon as they begin to look 'squared off' it's time to change them.

A new barrel spring hook was needed. It can be seen below that someone had attempted to solder the hook in. It came out with a little wiggle. A new hook was made on the lathe and fitted to the barrel.

After some pivot hole re-bushing work, pivot polishing/burnishing and a new pivot fitted to the escapement wheel arbour, the movement was reassembled and tested. After some finer adjustments to the escapements drops, the movement runs well and has proved reliable.

As mentioned the case was to get a light touch. The shellac on the case is a little wrinkled but is acceptable. The case had a dust and wipe down with some alcohol, followed by a high quality wax. New brass inlay was fitted where it was missing and the case was complete. The smudging of the numerals on the dial was improved as much as possible and the hands and screws were cleaned, polished and re-blued by heat.

I spent a great deal of time on this clock, far exceeding its value! But I think it was worth it. Please do send me any comments or questions you have, thanks for reading.